The Fight for the Sisterhood Phallus: A Psychoanalytic Examination of “Grave”

Julia Ducournau’s Grave views sisterhood rivalry through a bitingly horrific lens. The power hierarchy delegated by le bizuntage – the hazing culture of French university – along with the “sadomasochistic” and “gory” nature of a sisterhood carved down to its most primitive form stages Alexia’s violent and abusive relationship with her older sister Justine (Ducournau, 2017). Despite being placed at warring opposition in revulsive scenes of cannibalism and tactile horror, the two sisters’ mutually destructive behavior only strengthens their sisterly bond. The use of extreme violence as a catalyst for sisterly love – especially in the instance of Adrien’s cannibalistic murder – seems to undermine logical plot structure and supports a surface categorization of Grave as a splatter film, relegating the function of gore to the director’s self indulgence, or at best to a production of a cheap aesthetic mode. However, it is precisely such scenes of bestial violence and sexual decadence that develop a well-structured and complex psychoanalytic narrative between Justine and Alexia. With the film’s rigorous development of a psychoanalytic trajectory, the extreme relationship between Justine and Alexia is logically motivated, thus negating a reading of Grave’s gore as logically trivial.

Reading Grave as logically shallow is predicated by the criticism of the splatter film genre. The splatter film aestheticizes the experience of shock - prioritizing scenes that generate intense emotional effect (McCarthy, 1984). Briefly considering this aesthetic through Kantian theory, we can think of the tension between a viewer’s conceptualization of the film’s extreme gore – a function of imagination – and the viewer’s drive to rationalize such scenes – a function of understanding – as generative of a cognitive “free play” that mirrors Kant’s judgment of beauty (Paul, 2005; Giles, 1984). It is such cognitive “free play” that makes the splatter film thrilling to watch. However, since the experience of thrill is prioritized in the genre, the term “splatter film” is often used to dismiss a film as formally indeterminate without an “intellectual” narrative (Dickstein, 1984). Ducournau produces an overwhelming effort to match the splatter film’s primacy of the shock factor when establishing the unnaturally abusive relationship between Alexia and Justine. Their relationship is masochistic and bitingly violent, most dramatically evidenced when Justine and Alexia brawl in the courtyard and the two bite one another (Fig. 1). The hyperviolent courtyard brawl is completely uncharacteristic of the traditional notion of sisterhood and seems to indicate that Grave prioritizes thrill over narrative. However, if we assume that Justine’s relationship with Alexia does indeed follow a well-formulated structure, to discover this logical coherence, the sensitivity of psychoanalysis to the motivation behind such carnal violence becomes especially useful. Or else, if violence and sexuality in Grave exist within isolated spheres of shock factor, exclusively interpreting the film’s function as an aestheticization of gore becomes an incredibly strong justification for Justine’s extreme relationship with Alexia.

The evolution of Justine’s sexual indulgence introduces a component of taboo horror. However, narratively, this development serves to map out the formation of Justine’s libido. In Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, Freud defines the libido as the “energy, regarded as a quantitative magnitude... of those instincts which have to do with all that may be comprised under the word ‘love’” (Freud, 1921). Freud’s definition of libido is necessary to bridge the gap between a sexual coming of age and the emergence of Justine’s sexuality. Of the two sisters, Alexia is initially given exclusive sexual attention. The viewer is first introduced to Alexia through a sexualized image of her body, specifically, a center shot of her behind (Fig. 2a). In Justine’s establishing shot, the omission of eroticism, use of soft-lighting, and familial emphasis drawn through the shot of Justine with the family dog reinforce her innocence and heighten the contrast between the two sisters (Fig. 2b). As the film progresses, erotic attention is redistributed and Justine develops a much more erotic persona. After watching Adrien play soccer in the courtyard, Justine tries on the dress Alexia gave her and passionately kisses her own reflection (Fig. 3). This self-indulgent action, per Freud’s essay, On Narcissism (Freud, 1914), indicates Justine’s budding, yet unconstrained sex-drive. Justine’s experimentation with sexuality is predictable with Freudian logic – with her narcissism inheriting from the primitive, yet innate germs of sexuality existing freely in her subconscious, not yet coalesced into a unified libido.

A thrill-based reading of Justine’s experimentation with cannibalism is negated by attributing the habit to the failure of her libido to formally develop. The chaotic structure and raw audio design of the gothic punk rock accompanying Justine as she kisses her reflection emphasizes her libidal dissonance. Justine’s indulgence of narcissistic kissing along with the oral implications of “Fuck 69, give me 666” emphasize the fixation of Justine’s libido on the oral zone (Grave, 2016). This poses an immediate threat to Justine’s psychological growth, as Freud postulates that oral perversion (as we can interpret cannibalism to be) originates with the failure of libidinal development – that being, failure to develop past the oral stage. Justine’s exclusive interest in biting Adrien when the two engage in sexual intercourse further emphasizes her fixation on the oral stage. Justine’s oral perversion of cannibalism is then well founded considering her fixation on the oral stage. The bombardment of sexual, yet incongruous images parallels Freud’s characterization of the primitive libido, and its fixation on the oral stage structures a cannibalistic trajectory.

With the failure of Justine’s libido to move beyond a primitive stage, per Freud, the necessity for the libido to be directed towards an external object becomes especially pertinent. Justine’s affection for Adrien then becomes a subconscious effort to coalesce a libido around a well-defined love object. Justine’s affections for Adrien are evidenced by the composition of her perspective of Adrien playing soccer, which focuses on his chest and frames him in a soft light (Fig. 4). However, Justine cannot safely place her sexual desire on Adrien as Alexia also views him romantically, underscored by Justine’s immediate interjection of “hands off” when she fears Alexia might be serenading Adrien over videogames (Grave, 2016). Elaborating on sibling rivalry in a similar manner to Freud, Ducournau comments that there is a “fusion [towards a harmonious state of coexistence] that both [sisters] want to aim at, but that is impossible, because they are two different beings [with rivaling sex objects], so one of them has to disappear” (Ducournau, 2017). Both Alexia and Justine desire Adrien, yet only one of them can have him, thus there is a necessary fight for erotic dominance between the two siblings. This sexual conflict is substantiated by the transitional emphasis of eroticism between Justine’s first and last parties. In the first scene, Alexia is the primary sex-object – the center of erotic attention to the viewer (Fig. 2a), but in the other, Justine takes over this role (Fig. 5). In the latter, the position of Justine’s open legs, and the saturated red lighting of the scene indicate her desire to be seen erotically. Their erotogenic rivalry is once again seen when the two cannibalize one another’s arms in the courtyard (Fig. 1). Describing the formation of erotogenicity, Judith Butler in Bodies that Matter (1993) quotes Freud, reiterating the association between “the process of erotogenicity with the consciousness of bodily pain” (Butler, 59). The unwillingness for either party to back down from biting the other’s arm can thus be interpreted as emblematic of the unwillingness for either party to surrender their sexual dominance.

Familial sexual rivalry is readily modeled by psychoanalysis (ex. the Oedipus Complex), however framing Alexia’s relationship with Justine in a psychoanalytical model requires a parental designation. Object-relation theory defines an individual’s first-object as their internalized care-giver (St. Clair, 1986). By extension, an individual’s “first-object” is their internalized parental figure. Considering Alexia’s role results in placing her as a first-object to Justine. The composition of the initial party scene is hectic; the color scheme switches back and forth between dark red and purple (Fig. 6a, 6b), and the camera movement is incredibly shaky. In this chaotic environment, Justine’s solitary line of dialogue is “Alex” (Grave, 2016). Justine’s concern with finding her sister within the new and chaotic party environment hints to Alexia’s role as a primary object to Justine. Moreover, we see Alexia’s fulfillment of the primary object role when she thoroughly embraces Justine in the following scene, giving the younger sibling comfort and security (Fig. 7). Justine again seeks comfort in Alexia after Justine regurgitates strands of her hair. The two do not talk directly about Justine’s incident, but the comic relief provided by a scene of Alexia cleaning out cow feces, and her semi-inebriated recount of the time she “made out with a one-armed guy” ease the tension built by Justine’s regurgitation scene, emphasizing the calming effect the older sibling has on the younger (Grave, 2016). Alexia again takes on the role of primary object when she tends to Justine’s wounds after the two fight in the courtyard (Fig. 8). The soft lighting of this scene along with the position of both sisters within the same frame, compositionally equal at balanced vertical thirds of the screen, reinforce the affectionate sentiment between the two sisters. Even though abuse and rivalry are rampant in Justine’s relationship with Alexia, the preservation of the first object status of the older sibling is consistent with established psychoanalytic theory (D.S.W, 2009).

Alexia’s position as first-object, and thus the de facto parental figure of Justine, is genderless as constructed from the object-relation theory definition. To transition from object-relation theory to a psychoanalytical model requires gendering the parental role. Distinguishing between the paternal and maternal roles identifies whether Justine and Alexia’s relationship is based on an Oedipal scenario or an Electra one. In his essay, Female Sexuality, Freud rejects the integrity of the Electra Complex claiming, “it is only in the male child that we find the fateful combination of love for the one parent and simultaneous hatred for the other as a rival” (Freud, 1931). Temporarily disregarding static gender, Justine’s sexually rivalrous hatred for Alexia is inline with Freud’s characterization of father/son rivalries, thus permitting a designation of Alexia as the paternal figure. Moreover, Alexia’s abusive yet caring relationship with Justine is indicative of modern psychoanalytic understandings of the paternal role (Jones, 2005).

Completing a Justine-centered psychoanalytic familial model is Adrien’s definitive maternal role to Justine. After Justine is coaxed into eating a cadaver by her sister, it is Adrien who pulls Justine aside to make sure she’s alright. After seeing the video, Justine comments, “why didn’t you do something, why didn’t you help me?” (Grave, 2016). Her blame of Adrien is indicative of the maternal role Justine expects her roommate to fulfill. Moreover, when Justine decides to try meat for the first time, she trusts Adrien to accompany her and to keep her secret. We also see multiple instances of Adrien’s affection for Justine, first on the bus when Justine and Adrien go for sandwiches (Fig. 9a), and then when the two cuddle in the scene after Justine bites off a man’s lip at the blue and yellow paint hazing event (Fig. 9b). The hue of both scenes is a calm turquoise, emphasizing the affectionate sentiment between Justine and Adrien. Furthermore, even though Justine and Adrien eventually engage in a romantic relationship, their relationship is initially established as platonic. Adrien’s first line in the film establishes that he is gay; Ducournau comments that making Adrien gay reinforces his “tolerant look on [Justine], and [his] look of love for her” rather than his “sexualized look” on her. Ducournau’s use of “tolerant” and “love” corroborates the maternal characterization of Adrien (Ducournau, 2017).

At last, with the establishment of erotogenic rivalry between Justine and Alexia, and gender roles assigned to Justine, Alexia, and Adrien, we can apply Freud’s Oedipal scenario to the trio. Freud’s Oedipus Complex (described in Interpretation of Dreams¸ 1899) details the sexual rivalry existing between a son and father for sexual possession of the mother. With the roles of father, child, and mother corresponding to Alexia, Justine, and Adrien respectively, an Oedipus Complex scenario is formed that structures the plot of the film: Alexia has established sexual dominance over Adrien (the former being a “vété” and the latter being a “débutant”), but as Justine develops her sexuality, the younger challenges the older for sexual possession of the maternal Adrien.

Formalizing the Oedipal scenario, tension between Alexia and Justine manifests as competition for phallic ownership and fear of being castrated. When the two siblings attempt to urinate while standing upright, Alexia successfully accomplishes this endeavor, but Justine fails dramatically. The demonstration of Alexia’s control of the phallus confirms Alexia’s position as the paternal figure to Justine. Freud postulates that in an Oedipus Complex scenario, the child exhibits a fear of being castrated by the physically superior father as a result of the younger’s inability to successfully compete for sexual ownership over the mother (Freud, 1899). Likewise, Justine fears being castrated, screaming “No[!] You’ll circumcise me!” when Alexia suggests using scissors as a “plan B” for the botched Brazilian wax-job (Grave, 2016). The inclusion of the psychological drives behind the Oedipus Complex further justifies the application of the Oedipus Complex scenario to the relationship between Justine, Alexia, and Adrien.

A final complication remains for the application of the Oedipus Complex to the relationship between Justine, Alexia, and Adrien – the issue of the phallus. Freud’s use of the Oedipus Complex intrinsically involves the biological gender roles of the mother, father, and son. However, in the film, we see that Adrien plays the role of mother, Alexia the role of father, and Justine the role of son. Naturally, we get the question of how to assign the phallus. The use of non-traditional gender roles in the application of psychoanalytic theory is predicated by Judith Butler’s Bodies that Matter (1993). Butler deviates from the traditional male ownership of the signifier phallus, noting that erotogenicity (and thus the phallus) is “a property defined by its very plasticity, transferability, and expropriability” (Butler 61). Butler further quotes Lacan, stating that ownership of the phallus is synonymous to ownership of “the masculine position within a [societal] Matrix” (Butler 63). Within Alexia and Justine’s sisterhood, the necessity for an erotogenic hierarchy (the struggle for the “masculine position”) is formulated by the desire for exclusive sexual ownership of Adrien. Per Butler, a fight for ownership of a sexual object (Adrien), necessitates a fight for what we may call the sisterhood phallus – the dominant masculine position in the sisterhood. Consequently, irrespective of the absence of an anatomical phallus, we can apply the Oedipus Complex, driven by a metaphorical sisterhood phallus.

At a first glance, the peaceful conclusion of Justine’s relationship with Alexia is seemingly absurd; however, in light of the Oedipus Complex, it is clear how Adrien’s death removes the object of erotogenic rivalry between Justine and Alexia, thus resolving the Oedipal Scenario and subsequent erotogenic rivalry between the two sisters. After discovering that Alexia has killed and eaten her lover, Justine not only grants Alexia mercy, but precedes to bathe her in a maternal manner. The hue of this scene is soft despite the presence of blood dripping down both sisters (Fig. 10), contrasting previous scenes of erotogenic rivalry emphasized by vibrant red and purple lighting (Fig. 2a, 5). The reversal of the erotic color scheme hints to the resolution of the erotogenic rivalry. With the end of erotogenic rivalry, or fight for the sisterhood phallus, the Oedipal rivalry is necessarily dissolved. Alexia is reduced exclusively to first object to Justine, prompting the affectionate sentiment between the two after Adrien’s death – with the removal of Adrien, there is no psychoanalytic reason for the two to be in conflict.

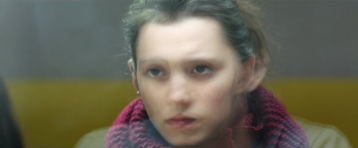

The continuing harmony between Justine and Alexia after Alexia is jailed is explained by the loss of plasticity of the sisterhood phallus. The hue of the scene where Justine visits Alexia in jail is a calm yellow indicating warmth and affection between the two (Fig. 11). The blending of both of their faces reinforces their harmony. Compositionally, Justine’s enmity towards Alexia is negated by the equally central position of both faces – undermining the chaotic vertical hierarchy of the rapid back-and-forth shots in scenes where the two sisters are in conflict (ex, Fig. 12, 13). Freud necessitates conflict if the ownership of the phallus is in question, or in this case, if the ownership of the sisterhood phallus is in question. After Alexia is placed in jail, dominance over the sisterhood phallus is no longer a driving force for Justine’s relationship with Alexia.

As stated previously, Butler quotes Lacan, defining ownership of the phallus as ownership of “the masculine position within a [societal] Matrix” (Butler 63). Once Alexia is in jail, the two sisters are no longer within the same societal “matrix”, and thus the conflict for ownership of the phallus is definitively resolved. With the removal of any possibility for future sexual rivalry, the two sisters assume an affectionate relationship.

Justine’s relationship with Alexia follows the trajectory of Freud’s Oedipus Complex. Through this psychoanalytical model, the random and chaotic dynamic of their sisterly bond is made methodical and well-founded. Much of the criticism Ducournau received for the film was centered around interpretations that the film was simply one that aestheticized extremity, with no other formal purpose than to be absurd and thrilling (Ducournau, 2017). However, it is exactly the inclusion of extreme and taboo scenes that builds a psychological narrative between Justine and Alexia. These scenes establish a first object relationship between the younger and older sister and develop a sexual rivalry that culminates to the film’s dramatic end. Without the film’s intense portrayal of sexual decadence and brutal violence an Oedipal narrative vanishes, so even while the gore in Grave can hold an aesthetic appeal, it also serves a structural function. It is precisely this doubled use of gore – as an aesthetic marker and a narrative device that elevates Grave from the splatter film. By examining the complex interplay between psychoanalytic theory and the film’s plot, Grave becomes a work worthy of academic study that experiments with gender-fluidity and non-traditional familial roles, ultimately testing the rigidity of modern psychoanalysis.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. Routledge, 1993, pp. 51-93.

D.S.W., Eloise Moore Agger. “Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Sibling Relationships.” Psychoanalytic Inquiry, vol. 8, 1988, pp. 3-30.

Grave. Directed by Julia Ducournau, performances by Garance Marillier, Ella Rumpf, and Rabah Nait Oufella, Petit Film, 2016.

Dickstein, Morris. “The Aesthetics of Fright” Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film. Ed.

Barry Keith Grant. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1984. pp. 36-49.

Ducournau, Julia, and Garance Marillie. “'Raw' Q&A | Julia Ducournau & Garance Marillier | Rendez-Vous with French Cinema.” YouTube, uploaded by Film Society of Lincoln Center, 21 March 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nz-jba7x_JE&t=601s.

Freud, Sigmund. “Female Sexuality.” 1931. Translated by Joan Riviere, International Journal of

Psychoanalysis, vol 13, 1932, pp. 281-297.

Freud, Sigmund. Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego. 1921. Franklin Classics, 2018.

Freud, Sigmund. On Narcissism: An Introduction. 1914. Ed. Joseph Sandler, Ethel Spector Person, and Peter Fonagy, Routledge, 2018.

Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. 1899. Translated and edited by James Strachey, Basic Books, 2010.

Giles, Dennis. “Conditions of Pleasure in Horror Cinema.” Planks of Reason: Essays on the

Horror Film. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1984. pp. 36-49.

Guyer, Paul. “Values of Beauty: Historical Essays in Aesthetics.” Cambridge UP, 2005.

Jones, Kim. “The Role of Father in Psychoanalytic Theory.” Smith College Studies in Social Work, vol. 75, 2005, pp. 7-28.

McCarty, John. Splatter Movies: Breaking the Last Taboo of the Screen. St. Martin's Press, 1984.

St. Clair, Michael. Object Relations and Self Psychology: An Introduction. Brooks/Cole Pub Co, 1986.

Articles copyright © 2025 the original authors. No part of the contents of this Web journal may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission from the author or the Academic Writing Program of the University of Maryland. The views expressed in these essays do not represent the views of the Academic Writing Program or the University of Maryland.