UMD English Ph.D. Students Are Helping to Chart New Field of 'Queer Bibliography'

July 10, 2023

Queer bibliography expands discipline to allow for a ‘more affective response to books,’ finds a home in BookLab.

By Chloe Kim

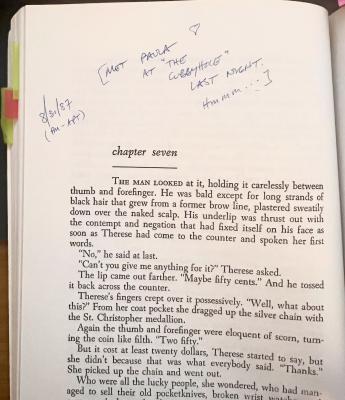

When English doctoral candidate Elizabeth Dinneny ordered a used copy of the classic 1952 lesbian novel “The Price of Salt,” it arrived to her with a surprise: dozens of scribbled notes in the margins, written decades ago by one of the book’s previous owners.

Reading like a personal diary, the notes contained a unique window into life in the ’80s in New York City: vignettes from lesbian bars, responses to the characters in the novel, even hand-drawn teardrops where the reader felt moved. Dinneny, who teaches a queer literature course in the Department of English, was fascinated.

“I started to realize it was really generative,” she said. “It was like a gold mine.”

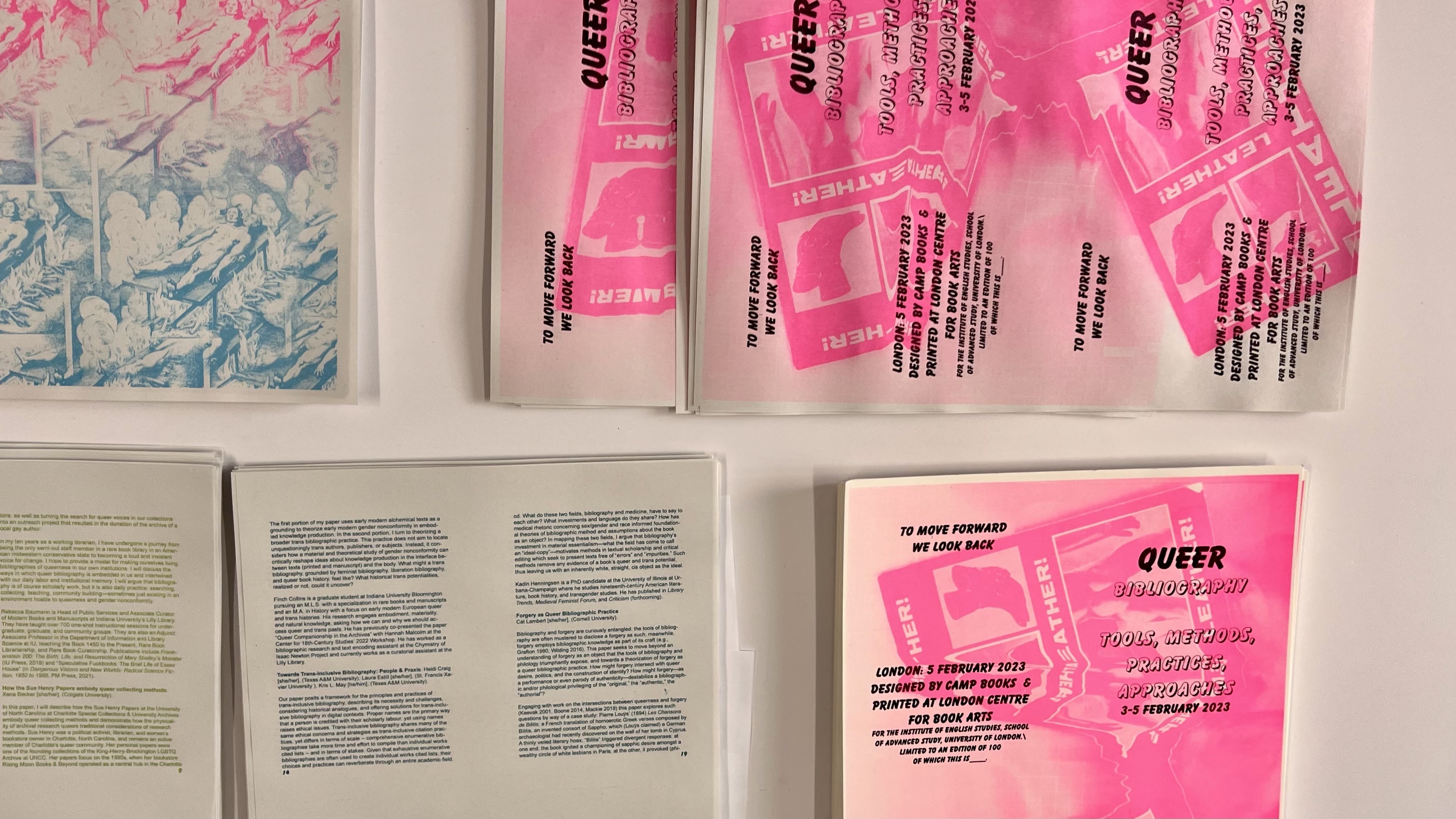

She began teaching the annotations in class, using them to empower students to share their own responses to the text. And earlier this year, she presented about the experience at an international conference devoted to the emerging area of “queer bibliography,” a new subset in the field of bibliography—the discipline of studying books as material objects—that encompasses scholars informed by queer theory as well as books containing queer content. Another UMD English Ph.D. candidate, Dylan Lewis, also presented at the conference, which was held in London and was the first ever of its kind. It drew librarians, book collectors, book historians and other types of scholars.

“It’s not that the work [of queer bibliography] hadn’t been done before, but it hadn’t necessarily been organized as its own field with its own specific methodologies,” said Lewis, who applied for the conference after learning about it from Matthew Kirschenbaum, a professor in the Department of English. “It was really exciting. It was definitely a new direction for the field and really cool that we got to be part of it.”

Within literary studies, bibliography has traditionally been considered a “scientific” discipline, one that considers books as physical artifacts whose contents are meant to be closely observed and researched. A bibliographer may, for instance, examine a centuries-old book and note that one of the letters in the text was printed with a damaged piece of type. By following the damaged type throughout the book, the bibliographer can infer how many pages were set and printed at one time, revealing the pace of work in the print shop and providing a glimpse into life in the 17th century.

In recent years, there has been a growing scholarly interest in the possibilities of opening up the field to new approaches, including through a queer studies lens. The California Rare Book School, for example, is offering a course in queer bibliographies this August that teaches students how to think critically about the way queer histories are documented in books and explore tools from various fields such as critical theory and library science to uncover queer identities of the past that have historically passed undocumented.

In 2024, Lewis and Dinneny will both have papers published in a forthcoming special issue of “The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America,” the Bibliographical Society of America’s journal, based on the talks they each gave at the symposium in London.

At UMD, queer bibliography finds a home in BookLab, the English department’s makerspace, letterpress printing studio, library and center for the book arts, where Lewis is an instructor. At the conference, he spoke about “queering bibliography” in BookLab by teaching through experiential—versus purely scientific—means: “Letterpress printing and crafting and hands-on fun activities in tandem with analysis and scholarly articles and observations,” he said. “So, we’re making stuff and playing around, and having fun.”

Kirschenbaum, who co-directs BookLab, said BookLab can continue to support the work of queer bibliographers and even “grow into a center for it.”

“I think we are opening space for a more affective response to books,” Kirschenbaum said. “Not seeing the bibliographer as a detached scientist, but rather as somebody who is invested, often emotionally. Queering bibliography helps to foreground those absences and gaps and what is ultimately knowable and recoverable from the past.”